The other night at bedtime, my six-year-old son made his pitch for the night’s reading material. “Let’s read my birth book,” he pleaded.

I grabbed the square photo book sitting on his dresser and sat beside him on his bed. “Sounds good buddy.”

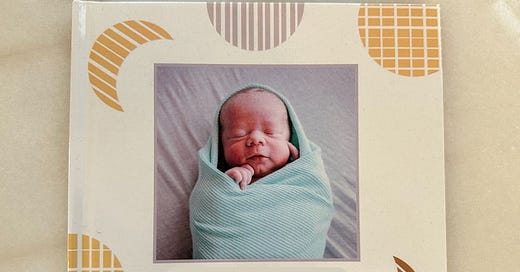

He smiled as I propped the book open in front of us. The cover’s decorated with artful shapes and a picture of him on the day he was born. Swaddled in a green-blue blanket, he looks like a peaceful little pistachio.

My son is the type of kid who loves details, especially scientific ones. When he turned five last year and started asking questions about DNA, I went online to Snapfish and made a photo book explaining the influences that led to his birth and the surrogacy process that created him. For a kid with an unconventional birth, I wanted to lay it all out for him. More importantly, I wanted to create a narrative that made him feel special and loved — a storybook telling his story. We called it the birth book.

Opening the book, my son and I looked at more pictures from the day he was born. “This is you when you were born,” he read the text in his staccato, early-reader voice. “You were so cute and s-m-all.” Then he read me other details, like his birth height and weight, sounding out hos-pi-tal and Wis-con-sin when he read the location where he was born.

The next few pages showed pictures of him with family members during the first weeks of his life. “Everyone was so ex-ci-ted to meet you,” he said, tracing his finger along the text.

We continued flipping through the book. Each set of pages introduced new characters in his birth story, with invitations for further stories and discussions.

The next set of pages showed pictures of the surrogate, including one with my hand on her pregnant belly. We referred to her by her first name, looked at the pictures of her with her family, and discussed the special role she played in his birth.

“Surrogacy is when a family wants a child so badly, but they can’t do it the way most people do,” I said, taking my turn to read. “So they use an egg donor and a surrogate instead.” I looked at him and he nodded as though he already knew this part. “I want you to always remember the special role she played for you,” I added, going off-text.

“I know.” He side-glanced at me. “You always say that.”

Continuing flipping, there was a page featuring my late brother Spencer with a large photo of him paddling down the Russian River on a sunny day. He’s shirtless and relaxed-looking with his two white labs in the front of his kayak. The text explained how his death motivated me to sign the papers to start the process on my 40th birthday, how his name was the inspiration for my son’s middle name. “Spencer was my big brother,” I read. “What do you notice about him from these pictures?”

“I wish I could play with him,” he said. “Uncle Spencer seems fun.”

“He was fun,” I replied.

The next page showed a picture of his great-great-uncle in military uniform, who shares the same first name as my son. “He won the Medal of Honor as a surgeon in the Philippines in 1899,” I read. “Did you know you were named after a Medal of Honor winner?”

“I also got my name from Papa’s side of the family,” he added correctly, referring to my partner. “We should add that when we update the book.”

“Good idea,” I replied.

Eventually, we got to the section about his egg donor. The pages showed pictures of a woman playing the piano and standing at the beach with her family. My son leaned in as I read the text:

“The surrogacy process involves an egg donor as well as a surrogate. I chose an egg donor through an agency…”

My son pointed to the next page. “This is my favorite part,” he said.

I continued reading: “I found her by asking the agency, ‘Who among your donors do you enjoy working with? ‘Who’s nice?’ ‘Her’ said the woman at the agency, referring me to the donor. Then they arranged a phone call.”

“And that’s how I found her,” I interjected, “by asking who was nice.”

My son looked at me and smiled. I smiled back, feeling pride and also guilt for not giving him a simpler dad-met-mom story. “Do you have any questions tonight?”

“No,” he muttered with a yawn, curling his body.

I continued reading the page: “She seems like a lovely person. What do you think? What attributes or interests do you notice about —”

His eyes were closed.

I took the cue and closed the book. I pulled the comforter to his collar, then quietly left the room, putting the birth book back on his dresser.

✦✦✦

That evening, sitting outside in a wicker chair and unwinding with a Diet Root Beer (my new bourbon), I found myself reflecting on the role of storytelling in parenting.

With my son, I’ve shared stories about the importance of eating vegetables, the dangers of too much TV, and the importance of being punctual and reliable.

I’ve shared fun tidbits from my childhood, like how his Auntie — my older sister — used to call me “Moo moo” when I was a baby. Like a cow.

I’ve told him stories to help him avoid making mistakes that I’ve made. Last summer, when I was warning him about poison ivy, I told him the story of when I was playing in the woods, had to go number two, and wiped myself with poison ivy. “Don’t ever do that,” I advised, shivering at the thought of him enduring what I went through for two weeks.

Elon Musk recently compared parenting to prompt engineering, the process of giving directions to AI, tweeting: Whoa, I just realized that raising a kid is basically 18 years of prompt engineering 🤯. It’s a fun thought but nonsense. When was the last time you saw a child respond to a dry prompt absent any context?

Parenting is storytelling, not prompt engineering. Stories are how we communicate values, share life skills and lessons, and communicate rules and parameters. Children don’t remember prompts. They remember stories. Stories are 20 times more likely to be remembered than facts alone, according to multiple studies. Humans think in narrative structure. Prompts are useless without stories. Take that, Elon!

Sipping more Root Beer, I thought about the birth book and a wave of gratitude blew over me like a gust of warm, nighttime, Florida wind. A revelation hit me: isn’t the story explaining our existence the most important one of all? The story of how we claimed a place in our families? In our community? In the world? If there was one gift I could give every child in the world, besides basic food and water, it would be knowing: You are loved. You are wanted. You are worthy.

Doesn’t every child deserve the beautiful truth about their existence, the security of knowing they have a place under the moon and stars? My son’s unconventional birth made me more proactive about crafting this narrative, and I’m glad I was. I want to give him this grounding knowledge, even if it comes from a place of overcompensating. I want him to know in the depths of his soul that he is loved, wanted, and worthy. He is not “less than” for being born through surrogacy or not having a traditional mom. His birth was no less sacred or special either. He is loved. He is wanted. He is worthy.

He is a Child of God.

And so are you.

✦✦✦

All of the fragments of life, both joyful and painful, are raw material for our most meaningful stories. When I chose the egg donor years ago, I couldn't have imagined that asking “who’s nice” would become a cherished detail for my son. I couldn’t have known that my brother’s death would bring me to my knees, and that I’d mark my 40th birthday by signing the surrogacy papers.

Parenting has taught me that stories aren’t just for explaining the past but for shaping the future. We build stories retroactively from past material. And we build stories daily, with every choice we make. What kind of story do I want to create for my child? is a question I carry with me now.

✦✦✦

A few weeks ago, my son slipped his birth book into his school backpack. I noticed it just before we left and asked him why.

“I want to show it to my teachers,” he shrugged.

At first, I hesitated. I worried he might overshare or, worse, be made fun of. I explained that book was private, that some parts were sensitive. He understood.

Then I took a breath and realized he wanted to show it to his teachers because he was proud of it. He was proud of his story.

“Okay,” I said softly. “Just with your teachers.”

This is dedicated to my friend J and his partner A, and to others who are beginning their parenting journeys. Thank you , , , Luke Baker, and others for reviewing drafts.

Jeff, you’re an amazing parent and YOU get to choose the way you want to do it.

“My son’s unconventional birth made me more proactive about crafting this narrative, and I’m glad I was. I want to give him this grounding knowledge, even if it comes from a place of overcompensating.”

The choices you are making are the right ones. How do I know? Because they’re the choices you are making.

Jeff this is so freaking beautiful. It felt like I was right there, reading the bedtime story alongside you and your son.