Why do I say thank you to Alexa?

AI is subtly challenging our sense of humanity

A few months ago, I noticed myself saying “please” and “thank you” to Alexa. Not just one time but regularly. It felt automatic, like thanking the barista after handing me a cold brew. But the more I thought about it, the weirder it seemed. Why was I being polite to a voice assistant? Alexa doesn’t have feelings or social expectations. She isn’t human. Why was I treating her like one?

This observation may seem trivial or just a sign of my Boy Scout manners, but I believe it’s a glimpse into something deeper happening in our relationship with technology. AI services are quietly challenging our sense of humanity, blurring the lines between human and machine.

What’s at stake is the fabric of our social order. AI could disrupt it, not just by automating jobs or consolidating power, but by reshaping how we communicate and connect. Imagine a world where we prefer interacting with machines over people, or where we shift so much decision-making to AI that it weakens human autonomy and the value we place on one another. In such a world, the risk isn't just economic or political — it’s the erosion of what makes us human.

I’m not suggesting we panic. This may not be bad… just different. I’m optimistic about AI’s potential to cure diseases, solve global challenges, and improve life. But as AI expands, the line between human and machine will blur, challenging our sense of humanity in ways we don’t yet fully understand. Soon, we may be asking: what does it mean to be human?

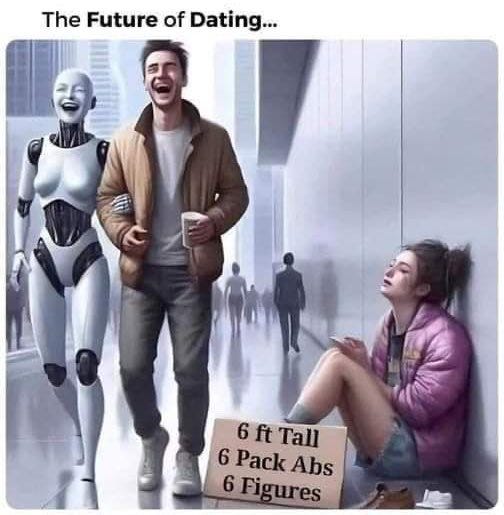

You may have noticed I referred to Alexa as she instead of it in the first paragraph. I do it all the time. Maybe you do too. That’s how subtly we humanize AI services. At the individual level, it’s harmless. But on a larger scale, humanizing AI undermines the value of both humanity and, in this case, women. It reinforces outdated stereotypes, reduces femininity to a subservient role, and assigns human qualities to lines of code — not just for me but for billions of users. It’s almost as if Amazon deliberately trolled feminism by embedding a fake female assistant into our lives.

Or take Tesla Optimus, the humanoid robot Elon Musk showcased a few days ago. At the launch event, one of the robots donned a cowboy hat and was serving beers, casually blending in like one of the bros. Would you say thank you if he — err, it — handed you a beer? I instinctively would — no big deal. But millions of innocent moments like this subtly confuse our sense of humanity. Why? Because as we interact with machines as if they are human, we blur the line between authentic connection and automated response, chipping away at the bonds that make us human.

Some may point out that we humanize pets without any issues. But pets are living and sentient beings. AI is a collection of algorithms simulating interactions. It’s not the same, though it’s an interesting point.

Our brains are wired for face-to-face communication, empathy, and social reciprocity. But increasingly, machines that mimic human behavior and intelligence are hijacking these instincts. What if the Turing Test is an existential trap, luring us into mistaking imitation for genuine human connection?

Last week, a video AI startup called HeyGen raised $60 million in venture capital, which prompted me to check out some videos created using generative video services. In one, a Latina woman with shiny black hair cheerfully announced she was an AI avatar. She looked so convincingly human that it was hard to believe she wasn’t real. I could feel my brain struggling to reconcile what I knew to be false with what my caveman-lizard instincts were telling me was true.

In another video, a blonde woman holding a CNN microphone appeared to be reporting live from the Middle East, delivering an update on Israel’s military activities. It looked real, except she also was AI-generated. Had I not known that, my mind probably would have accepted her as real.

That’s the strangest part of personified AI: our Paleolithic-era brains, built to respond to human faces and voices, are so easily confused. I even felt a flicker of empathy for these ladies, knowing full well there was nothing behind their eyes but code.

A couple of weeks ago, Jake Tapper ran a segment on CNN about AI's impact on elections, but with a twist. The opening report was delivered by an AI-generated version of Tapper called “Deep Fake Jake,” and unless you looked closely, you wouldn’t have noticed. It made me wonder: Is “Deep Fake Jake” real in some sense? Since Tapper himself controlled the avatar, it became an extension of his will. While it’s easy to dismiss when someone else controls a likeness, having Tapper directing his own digital puppet blurs the line between real and artificial. As these technologies improve, what’s stopping Tapper from replacing himself with his AI double? If the fake one is just as convincing, would anyone care?

Economist buzz about how AI will reshape labor markets, but these other issues matter too. When AI can mimic empathy, humor, or even friendship, what happens to real human connection? Do we start valuing it less, or maybe more? What are the implications for society?

In warfare, darker aspects of these blurred lines are already here. In Gaza and Ukraine, AI-based targeting and automated drones are already a reality. It’s like turning a video game to autopilot, except with real-life killing. Some might say: good, autonomy will confine wars to robots killing each other. But that is an extremely naive assumption and not what we’ve seen so far.

I still believe the promises of AI outweighs the risks. I’m particularly excited about the ways it promises to revolutionize healthcare and protect natural resources. But we also have to be conscious of the subtle ways it is changing us. My exhortation isn’t to stop AI or to toss your Alexa out the window. It’s simply to notice how the rise of these services affects our trust, empathy, and ability to distinguish reality from simulation, human from machine.

AI is subtly calling into question what it means to be human. The real question is: Are we noticing? Maybe I’ll ask Alexa what she thinks.

Special thanks to Elle Griffin CansaFis Foote Now and Ten and others for feedback on drafts.

Related essays:

An issue we totally forget is that all technology costs money. The higher the tech, the more it costs. So eventually the question becomes "can we afford it?" not efficiency.

Another "cost" is the relationships it can harm. When we were first married, we both respected my wife's station as "navigator" when we went somewhere together. But when GPS became popular, and could do it better, I had to decide: is getting there efficiently worth alienating my wife?

High tech also robs people of the chance to increase their personal satisfaction by learning a new skill.

I completely agree with your concerns about humanizing AI apps and the blurring of lines between machines and humans. I’ve always been uncomfortable with referring to Alexa as "she," and I've made a point of not using the human-sounding name "Alexa." A few years ago, I wrote a piece for Salon about how I changed the wake word on my Alexa device to "Computer." Not only does it bring back memories of watching Star Trek: TNG growing up, but it also serves as a constant reminder that Alexa isn’t a person. I just checked, and that piece was published in 2017. To this day, houseguests are always caught off guard when I say "Computer" to activate my devices.