The Lamplighter Problem

the world needs to discuss the broader ramifications of AI and mass job displacement

For we are all very lucky, with a lamp before the door

And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more.

- Robert Louis Stevenson, “The Lamplighter” (1885)

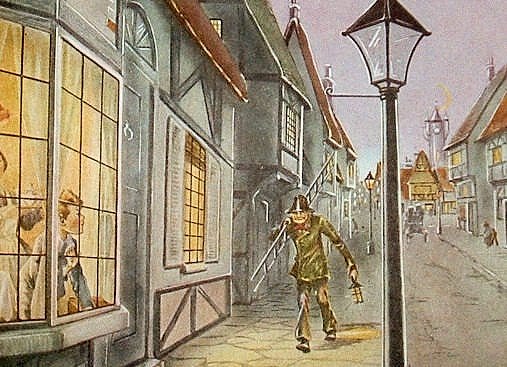

I wonder what it was like to have a friendly lamplighter like Leerie in the neighborhood, making the rounds each evening to manually light the street lamps. Stevenson’s nostalgic view of the lamplighter is similar to how older generations may remember milkmen — friendly faces and unofficial watchmen in the neighborhood. By the early 20th century, lamplighters like Leerie lost their jobs as gas lamps were replaced by electric lighting. Some were retrained for electrical work; others moved on to industrial and municipal jobs.

Today, hundreds of millions of people face a similar fate as the lamplighters. McKinsey estimates that AI-driven automation could displace 400 to 800 million global workers by 2030.1 Looking ahead, I can’t help but wonder: What will happen to humanity as smarter machines take over? How can society cushion the impact? I think about these issues as a dad, as well as someone at the intersection of technology and politics.

We are all “Leeries.” AI is sparking a labor revolution as profound as the Industrial Revolution, affecting every role in the global economy — port workers, lawyers, designers, and more. The stakes couldn’t be higher: the future of the economy, democracy, and humanity itself. Yet public discourse is trailing the technology by, like, a decade. It’s like a tsunami is approaching and we are sipping Mai Tais, discussing last week’s weather. If we don’t catch up fast, AI will reshape the world before we even realize it, making the revolution a fait accompli. By raising awareness and advancing public discourse now, we can still control our destiny.

We need a shorthand for the challenges ahead, which is why I’m calling it the Lamplighter Problem — a term that captures the broader impact of mass job displacement across politics, society, and the economy. Inspired by Stevenson’s poem, it evokes the tsunami-like disruption AI will bring. The lamplighter metaphor works because it’s timeless, symbolizes someone who literally brightened the world, and humanizes both sides of the displacement.

Both Sam Altman and Curtis Yarvin have recently touched on these themes through the figure of the lamplighter. Altman, CEO of OpenAI, invoked the lamplighter in his essay “The Intelligence Age,” offering an optimistic take on AI’s future.2 “Nobody is looking back at the past, wishing they were a lamplighter,” he noted, highlighting how technology has advanced human progress.

In contrast, Yarvin argues in a response titled “Sam Altman’s Lamplighter” that we should wish more people were lamplighters today.3 To Yarvin, it is better to be a lamplighter than an idle welfare recipient collecting UBI checks and binge-watching Netflix. Work, in his view, gives people meaning, dignity, and purpose. He advocates creating traditional, artisanal jobs to counter automation’s destabilizing effects, a sort of large-scale Etsy economy. I’m not certain that’s the solution, but I strongly agree with his core point: automation isn’t just an economic problem — it’s a political one. Yarvin rightly points out that displacement caused by the Industrial Revolution gave rise to communism. If we push automation too hard without addressing its impacts, the political consequences could be dire. Enslavement by robots? Fully automated Stalinism? No thanks!

As I read their essays, I couldn’t help but picture Leerie and the many “Leeries” in my life today. I know both Altman and Yarvin, and I’m friendly with many in the tech world. At the same time, I have loved ones whose jobs could someday be automated, while others are question marks. Will my nephew beginning his career as a commercial pilot be displaced by autonomous planes someday? I just don’t know. I feel anxious thinking about it. So I find myself of two minds: AI excites me, and I want to accelerate into the future. But I’m also wary of the upheaval it will cause. This transformation could displace millions, destabilize lives, and challenge the structures that give people meaning and purpose, including democracy itself. This personal conflict mirrors the broader societal tension, which is why we need a shorthand like the Lamplighter Problem to discuss these challenges.

At its core, the Lamplighter Problem asks us to consider how to maximize human flourishing and empowerment in the coming “intelligence age.” How do we make sure the AI tsunami benefits human freedom and autonomy, and that these benefits are shared? That’s my north star, and I suspect many would agree, though it’s still worth debating. But even with a shared north star, people will have different ideas for achieving it. For some, advancing human flourishing will mean standing in the way of AI advancements yelling STOP. For others, it will mean accelerating AI at full throttle, yelling GO GO GO. Most of us will find ourselves somewhere in between. My approach leans toward GO, but with pragmatic caution.

This isn’t theoretical. We already see versions of the Lamplighter Problem in action. Take, for instance, the recent labor dispute involving Harold Daggett of the International Longshoremen Association, a key figure in the fight over port automation. At first, I thought: Automate the ports! To hell with this guy and his union for holding America’s supply chain hostage before an election. Economically, automating our ports as they did decades ago in Rotterdam is a no-brainer. But when I consider the thousands of jobs at risk, the ripple effects across families and communities, and multiply that across hundreds of other professions, the Lamplighter Problem becomes clear. It reminds me that these issues require a humble, thoughtful approach.

As a society, we must face the Lamplighter Problem head-on. We have to talk about it. By naming it, I hope we can foster a conversation that looks beyond the horizon to the social and political fabric of human flourishing. But that’s just one step. We need to broaden awareness and advance the discourse on these issues, from barstools to legislative halls. I will do my part. In a future essay, I will map out different schools of thoughts and various solutions that have been discussed so far.

In the meantime, maybe it’s wise to let Leerie light the lamps a few more nights.

Special thanks to and others for feedback on drafts. I want to know your thoughts! Please share in the comments. Below is the full poem.

The Lamplighter

by Robert Louis Stevenson (published in 1885)

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky;

It’s time to take the window to see Leerie going by;

For every night at teatime and before you take your seat,

With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street.

Now Tom would be a driver and Maria go to sea,

And my papa’s a banker and as rich as he can be;

But I, when I am stronger and can choose what I’m to do,

Oh Leerie, I’ll go round at night and light the lamps with you!

For we are very lucky, with a lamp before the door,

And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more;

And O! before you hurry by with ladder and with light,

O Leerie, see a little child and nod to him tonight!

The argument for keeping lamplighters reminds me of Milton Friedman's argument about make-work jobs:

At a canal-digging project, Friedman's hosts were eager to show the many laborers working to excavate a canal. But Friedman was more interested in the lack of modern machinery on the site. He asked why they relied on human labor to do a job that would be more easily and quickly done with modern machinery. “This is a jobs program,” came back the reply. Friedman responded that he had mistakenly thought they were building a canal. If they were only seeking to provide extended employment to many workers, he said, they would need even more if they handed out spoons for digging, rather than shovels.

Looking forward to hearing more about this! Maybe the solution isn't hard labor sinecures, but soft labor ones. Like social clubs, aids for the lonely, things like that? Maybe you're getting to that. . . Lamplighters who shine lights of hope and connection