Today’s world feels increasingly contrived, synthetic, and disembodied.

But I have good news: I’m learning to live in what French philosopher Jean Baudrillard called “hyperreality” — a state where the distinction between reality and simulation collapses. I’m already immersed in synthetic experience, surrounded by simulacra. And I think it’s going to be okay.

There are still paths to the good life — to shared reality, human connection, and meaning — that cut through today’s postmodern confusion and techno-cultural saturation. Yes, friends: Beauty, love, and truth are still within reach.

Three scenes from a recent trip helped me see this more clearly.

Scene One - Paris

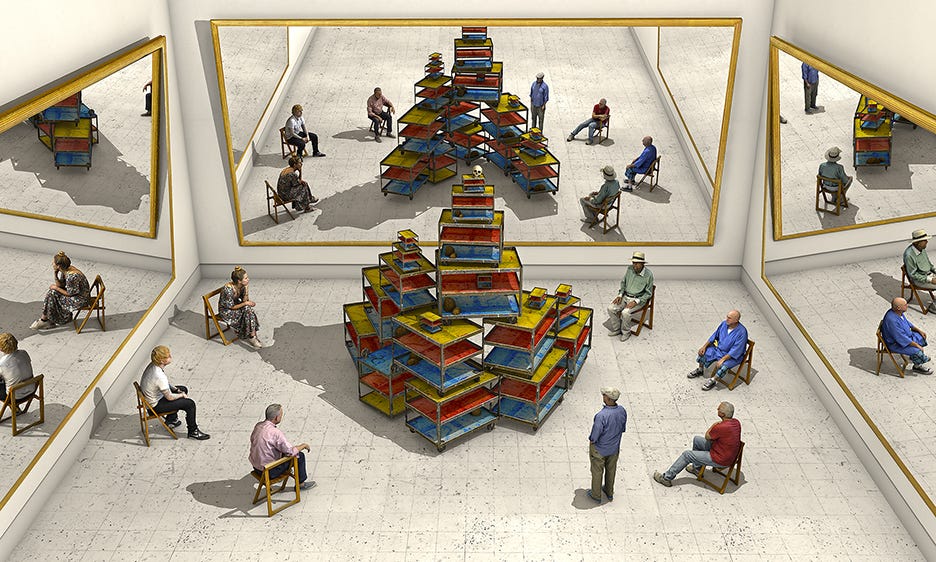

Inside the Louis Vuitton Foundation, a fabulous Frank Gehry structure on the edge of a park in Paris, I’m staring at a painting by David Hockney, part of an extraordinary exhibition of his work.1 It depicts a group of people looking at a sculpture in a hall of mirrors. A skull sits on top of the sculpture.

Hockney brilliantly captures three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. The painting is a series of reflections. It’s easy to get lost in them, raising the question: What is real? As I stare, something shifts in my body. I fold my arms, feeling the warmth of skin against skin. I realize: in a world of mirrors, we must never lose sight of what they reflect — ourselves, our own material reality.

But a question lingers: What does the skull mean?

Earlier that day, I’d learned something strange: Foucault died of AIDS after reportedly dismissing the disease as a fantasy of American puritanism.2 Imagine the tragedy of denying the material reality of a disease while dying from it, of being undone in part by one’s own worldview. To be fair, this was in 1984, in the early days of AIDS. But I felt angry at him and at this mindset. It made me think of the relative who refused COVID vaccines and then died of the virus months later. His wife is still antivax in her seventies.

Maybe the skull in the painting was theirs.

How long can we afford to play this game of deconstruction?

Scene Two - Strasbourg

A few days later, I’m walking through the center of Strasbourg, wearing AirPods, a veritable Headphone American. The old city is magical: canals, gingerbread architecture, a towering Gothic cathedral.

I’m standing in front of a statue of Gutenberg, chatting with ChatGPT in voice mode. The voice I’ve selected, "Ember," sounds like a friendly male guide from Northern California.

Ember explains that Gutenberg lived in Strasbourg from 1439 to 1444, working on his press. At the time, Strasbourg was a Free Imperial City, a hub of free thought and innovation. He points out the inscription in Gutenberg’s book: Et la lumière fut — "And there was light," representing Gutenberg’s impact on the world. Each side of the statue’s base depicts knowledge from a different continent.

I step back and chuckle. How funny to learn about the inventor of the printing press… through artificial intelligence. I marvel at the historical echo linking one civilizational technology to another.

ChatGPT was my secret tour guide throughout the trip. I used it for itinerary suggestions, historical context, and playful experiments. In Paris, I snapped a photo of a mysterious sphinx statue along the Seine, uploaded it, and received a detailed explanation. It was a common Greco-Roman-inspired design of a sphinx with a lion’s body and a woman’s face. I was impressed.

Gazing at the statue, I wonder: will AI illuminate the world the way Gutenberg’s press once did? Will someone like Sam Altman deserve a similar statue?

The printing press was a technology of distribution, mass producing books and pamphlets. AI, by contrast, is a technology of synthesis. It distills and generates information from vast datasets. The printing press promised knowledge for all; AI promises intelligence for all.

But what AI creates are simulations — approximations of human insight, knowledge, and expression. AI is, in many ways, a technology of simulacra. Much like Hockney’s painting, it’s images reflecting images, endlessly.

The printing press fueled the Reformation and the Enlightenment. But it also unleashed chaos, upending political structures, fueling religious conflict, driving polarization.

We really don’t know what AI has in store for humanity. Even if it’s as positive as the printing press, it’ll likely sow its own historic disruptions. What is the cost of light? Will it be worth it?

I turn away from the statue and walk to the Cathedral, where Ember tells me about the history of the cathedral and its impressive astronomical clock. Having on-demand voice access to the world’s knowledge isn’t so bad, I realize.

Scene Three - Zurich

In Zurich, sitting outside at a cafe with outrageous prices, crammed tables, and spring bursting with vitality, I strike up a conversation with an older British couple driving across Europe. At one point, the woman laments how Maps has shifted their relationship.

“I used to be our navigator,” she sighed. “Now I’m no longer needed.” She’s half-joking, but there’s real loss beneath it.

I tell them about a recent drive to Orlando, how I had to change the voice guiding us in Maps because it annoyed me. We laugh.

I love Maps. I depend on it constantly, especially when traveling. Most of us do. Yet it’s completely synthetic. A disembodied voice has taken over.

Something human has been displaced, yet we’re okay with it. In fact, we like it. It makes life easier.

And despite it, the British couple still loved each other. I could tell.

Beyond the Hall of Mirrors

We are already living in hyperreality, I realized during the trip. Baudrillard warned of it decades ago, before cell phones, the Internet, and AI. And here it is — as he warned but more globalized, virtualized, and tech-enabled than he could’ve imagined.

Today, daily life is constantly mediated by synthetic experience: Maps, grocery self-checkout, Alexa, personalized algorithmic feeds. On one level, Baudrillard was a Cassandra, warning us of this flood of synthetic fakery devoid of meaning.

But on another level, Baudrillard and postmodernists like him have given us nothing beyond nihilism. They placed us in a hall of mirrors, locked the door, and walked away. As if saying: Everything’s fake. Good luck! Worse, they chased their theories into absurdity. Foucault refused material reality even as it claimed his life. Baudrillard embraced nihilism, even celebrating it as “jubilant.” At some point theory collides with fact, even for postmodernists in denial.

My point is this: Deconstruction may provide insight, but it isn’t an end point. Hyperreality may be real, but it’s not an excuse for post-reality. Just because the human and synthetic blur together doesn’t mean we can’t find our bearings. We still have agency. We still have values. The idea that everything is simulation creates a permission structure for nihilism, moral collapse, and magical thinking. It’s intellectually lazy and emotionally adolescent. We need to move beyond it.

Postmodern ideology may have emerged from the left, but its effects are bipartisan. When people accuse Trump of being post-reality, they have a point: his politics are postmodern on some level. Narrative replaces reality. Facts become optional. But abandoning reality isn’t good for humanity. Epistemic health — the foundation for fact-based discussion — is a baseline for civilizational sanity and democratic cohesion. Probably personal sanity too.

Yes, synthetic experiences will continue to shape our lives. Yes, the man sitting next to us on the subway may inhabit a wildly different media and cultural reality. But meaning, beauty, love, and humanity are still real. Facts matter. We may be surrounded by mirrors and periodically confused by them, but we aren’t trapped in them.

We can still find reality in the reflections. We can still sit in the chair, feel the weight of our body, and breathe in and out. We can hold our breath until our body demands we exhale. And it will.

A virtual reality headset won’t stop someone’s cancer. But it won’t take away their capacity for love, either.

Reality persists, even in hyperreality. So do human experience and meaning — if we choose them. Our challenge is to forge a good life beyond the postmodernists, beyond the mirrors. This means reconstructing rather than deconstructing.

Loved sinking into these vignettes. Felt immersive and "real."

Agree that the sense of hyperreality can become an excuse for nihilism, and agree just as hard that it doesn't have to be. Here's to finding the most meaningful, ethical arrangement of the mirrors.

This brought my fav novel Infinite Jest to mind. DFW doesn’t just show hyperreality as disorienting but perhaps more importantly as numbing. The danger isn’t that we just mistake simulation for truth, but also that we stop caring whether there’s a discernible difference. The characters aren’t undone by lies necessarily, but ultimately by the comfort they afford. DFW's answer isn’t to escape into some collapsitarian fantasy. Instead it's to pay attention abd accept a certain level of pain. To choose meaning, even when every system around you is built to dull it, or worse yet make you doubt it's possible.