Delete or die

Against the tyranny of total digital memory

Data is becoming the defining force of modern civilization. Many aspects of it are amazing, like AI medical breakthroughs, Netflix recs, and instant access to the world’s knowledge. But this ethos of data über alles is also reducing our humanity to bits, denying our need to forget, and collapsing the line between reality and simulation. We are slouching — no, racing — toward total digital memory. I want to stand athwart it, yelling: Stop! Some things are meant to be forgotten!

Permanent digital memory is the default setting of modern life. Our devices back up every message. Google makes everything clickable. Credit cards track every purchase. There’s always a rewards program, biometric scan, or new app to download. The average person generates 5,000 data interactions per day.1 Even the privacy-minded produce mountains of data exhaust. It’s inescapable. This is why data centers are spreading like locusts, devouring global energy.

Yes, the rise of digital memory is driven by technology and economics. But its impact is civilizational. Every interaction feeds a digital ledger of our lives that’s permanently archived, resurfaced by algorithms, and often resurrected by AI. It’s like a sci-fi version of the high school “permanent record,” or the Stasi in The Lives of Others, scaled across global civilization. This has profound effects we’re barely beginning to understand. And we haven’t stopped to ask if it’s something we actually want.

You don’t have to be an off-grid farmer or Unabomber type to appreciate this. 92 percent of Americans worry about their privacy online.2 The vast majority feel they have little control over what the government or corporations do with their data. Most believe they can’t go through life without their data being collected.3 I love technology. I use data-driven tools all the time: ChatGPT, health-tracking watch, endless digital photos… and that’s just in the last hour. I’m not telling people to be digital hermits.

But we should have more say over our digital footprints. It’s a mistake to blindly allow all of our data to be stored forever, trained on, and immortalized. Total digital memory may sound like progress, but it profoundly threatens our agency. It opens the door to creepy new forms of authoritarianism, warps how we relate to each other, and blurs the line between actual memories and simulations. For individuals, it means more anxiety, less privacy, and constant surveillance.

As the world trends toward remembering everything, our humanity depends on creating new space for forgetting. We need to be more intentional about what we preserve and what we let go, or we’ll entrap ourselves. We need a new ethics of digital memory — quickly. Total data surveillance is already at the doorstep. This is why some people are freaked out about Palantir, and I get it. Imagine the Patriot Act with a corporate panopticon. Either we develop a culture of intentional forgetting or we exist in an archive we can’t escape.

The basis of biology is a cycle of life and death. Humans evolved forgetting as a way to prioritize brain power, create social harmony, and cope with life. But data is immortal and immutable. Today, these two forces — the mortality of biology and the immortality of data — are at odds. We need to reconcile them, or things will get freaky fast. Imagine someone sending you messages in the voice of a dead relative, physically cloning someone based on a loose hair, or building personalized bioweapons based on your leaked 23&Me data. These possibilities are imminent.

Anyone with a Googleable name knows that digital memory can be a bitch. Even if we want to reinvent ourselves or close a chapter, old content lingers like an unwanted guest. To live in today’s world is to bargain with digital memory: how much to post, what to save, what to delete. Even writing this essays is a tradeoff. I get to express myself but lose privacy. Once I hit publish, I lose control over its memory. Someone could archive it, and it could live online forever even if I deleted it here. Is it any wonder Zoomers and Millennials are suffering from so much anxiety, having grown up in a world where the default is to digitally archive every goddamn thing?

Ed Sheeran’s song “Old Phone” hit me hard when I heard it. It’s about finding an old phone and confronting frozen fragments of the past. “Conversations with my dead friends / messages from all my exes,” he sings. Then he reflects: “I kinda think that this was best left / in the past where it belongs.”

As Sheeran poignantly suggests, there’s something sacred about letting the past remain in the past. When my brother Spencer died, the last voicemail he sent me sat on my phone for months. It was the full arc of a psychotic episode — paranoia, vitriol, then a flicker of love at the end. Mostly crazy-talk. Still, it was his last message, and I’d re-listen to it through my grief. Eventually, about six months after he died, I listened one last time, took a breath, and hit delete. It felt like a betrayal, then like a release. I decided: This isn’t how I want to remember him. It was a simple deletion but also an act of authorship over my memory, a way to protect it. We all face this kind of choice when someone dies, a relationship ends, or a chapter closes.

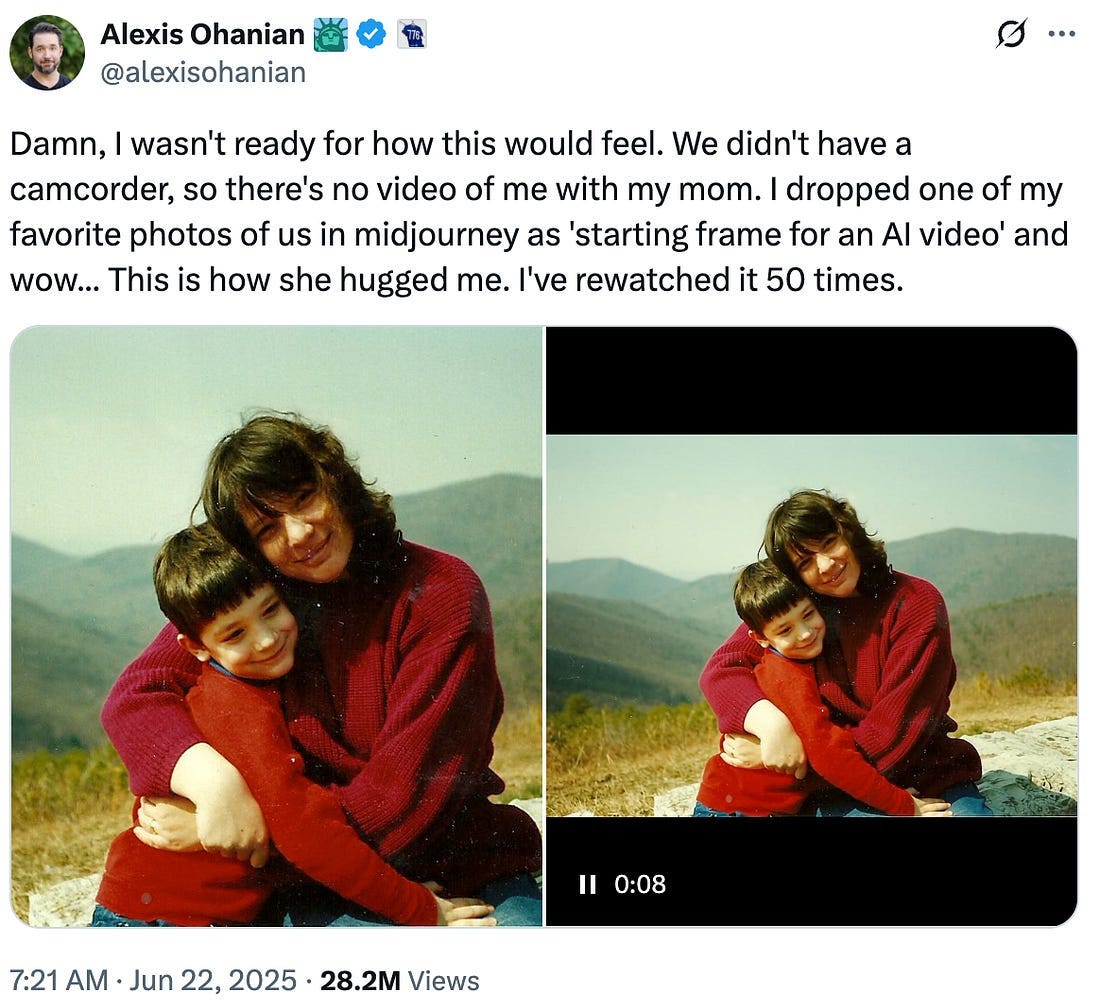

Alexis Ohanian, the founder of Reddit, recently tweeted a childhood photo of himself and his late mother hugging against a mountain backdrop. Alongside it, he posted an AI-generated animation of the image. Their faces blinked. His mother looked at him adoringly, alive again. Ohanian said it made him emotional, and I believe him. The video felt real and moving, but also like it skirted the line of something sacred.

I’m not saying Alexis was wrong to do this. For some, digitally reviving a loved one may be comforting. And Alexis did it himself; it’s not like someone else forced it on him. But we should be cautious about where this goes. Cloning voices and animating photos may seem harmless, but a future where people make AI replicas of dead people isn’t far off. Perhaps the most human way to honor the dead is not to bring them back. Forgetting is how we protect what is sacred. Life is for the living, yet data memory clings to the past.

Some might ask: is there any difference between animating an old photo and finding a VHS tape of the same moment? And I think the answer is yes. The difference is simulation. Recordings document reality; AI simulates it. These digital resurrections live in an uncanny valley of hyperreality. Biological cloning would only complicate that weirdness further.

Here’s the point: Forgetting is essential to human agency. Forgetting is freedom. Forgetting is how we protect the sacred, including memories of the dead. And we desperately need to forestall the tyranny of total data memory.

Thankfully, our culture is slowly adapting. There’s a post-cancel culture recognition that digital memory is a burden we all carry; overlooking stupid things from the past has become a kindness. New messaging apps like Signal provide the ability to automatically delete messages after a certain period of time. I love using this feature because it frees me from having to wonder, “How’s this going to age?”

A friend once explained the difference between artifacts and ephemera.4 Artifacts are meant to endure. Ephemera are meant to fade. It’s a useful framework for reasserting agency over digital memory. We shouldn’t have to default to digital memory for everything. I want some of my essays to be artifacts my kid can read when I’m gone, but I don’t feel that way about tweets. Essays are potential artifacts; tweets are ephemera.

As data continues to drive human civilization, we must become more deliberate about the other side of digital memory: forgetting, deleting, moving on. Policy solutions like the right to erasure, ownership of biometric data, and deeper consumer privacy protections could help. Tech services could make it easier to flush data, encrypt and anonymize information, and offer settings that allow auto-deletion. Culturally, we could do better as a society at knowing when to let things go. Imagine a kind of statute of limitations on digital memory, as a norm.

We’re sleepwalking into a tyranny of total digital memory. This is a call to wake up. We need to take back control of our digital footprints to protect our freedom, our agency, and our sacred memory.

To be human is to forget.

Special thanks to for feedback on an early draft.

Interesting distinction between artifacts vs ephemera and the “uncanny valley of hyperreality”. I had a similar reaction to the Alexis tweet. In that limited form it seems harmless and is very valuable for him. But the implications of what that could mean in the future, the ways old video and images could be manipulated, fictional scenes from the past could be spun up in no time. Makes my head spin a bit

…if we don’t own our online self then what value is there to having one…